Perhaps the most appropriate summary of modern transportation is “the car”. It is an invention only a century old, but it literally and fundamentally changed the way civilization works: this is equally true in the business, social and cultural context. Millions of people drive to work tens of kilometres from where they live, asphalt has in a sense become a criterion for measuring the reach of civilization (one can hardly talk of civilization in any place detached from the global road network), classes of cars have become status symbols and so on. The same way the Vespa liberated a generation of Italian youngsters during the ’50s, the car is seen today as a precondition of a free and comfortable life in the West. People in the rest of the world desire it, but it is still out of their economic reach.

Perhaps the most appropriate summary of modern transportation is “the car”. It is an invention only a century old, but it literally and fundamentally changed the way civilization works: this is equally true in the business, social and cultural context. Millions of people drive to work tens of kilometres from where they live, asphalt has in a sense become a criterion for measuring the reach of civilization (one can hardly talk of civilization in any place detached from the global road network), classes of cars have become status symbols and so on. The same way the Vespa liberated a generation of Italian youngsters during the ’50s, the car is seen today as a precondition of a free and comfortable life in the West. People in the rest of the world desire it, but it is still out of their economic reach.

The car has had its problems, too, and we will get to them in a moment, but it is important to notice that the global automotive industry is effectively addressing one issue and one issue only: electrification, the cause of the current hybrid and electric drive hype. What car makers are working on is increasing range and decreasing price of electric cars, mostly because people no longer feel as comfortable as they did burning petrol to move around and because people assume hybrid and electric vehicles do less damage to the environment.

Knowing that for every 100 litres of fuel burned about 2 litres are spent on actually transporting the driver from point A to point B (details below), one has to be grateful that a major efficiency problem is being looked into. However, there are two issues with the effort. One is that it is not at all obvious that hybrid or electric cars are, in fact, more sustainable: the ICE Citroen C1 has almost the same efficiency as the much touted Toyota Prius hybrid, for example. The other, much more serious problem, is that car transportation has so many other serious problems that it boggles the mind that car transportation is considered a viable platform for mass transportation at all, let alone that it is actually implicitly labelled as the only such possibility.

If you haven’t given much thought to cars as a form of mass transit yet, the above statements are probably, well, quite hard for you to relate to the real world outside, but allow me to explain and substantiate with references…

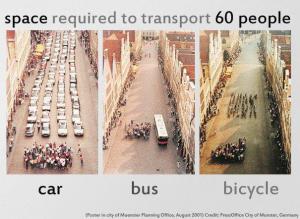

Highschool physics tells us that a typical car travelling at 60km/h has a kinetic energy of roughly 200 kJ, about the equivalent of raising a man to the 100th floor of a building. The fact that a car accumulates such an astounding amount of kinetic energy during regular use is one of the most important facts of road transportation with many and far reaching consequences. One obvious and direct consequence is that a moving car is very difficult to stop. In spite of state of the art break technology, most cars need tens of meters to come to a stop, and that is just in urban traffic: in inter-city traffic it easily grows to more than a hundred meters. Because they require so much space to achieve even today’s shameful safety track record, urban motorised traffic is a kind of pulsating, twitching process: cars go, than stop, than go, than stop and after a certain number of such cycles they arrive at a destination. Because they spend a lot of time idling in a queue, taking up all the room that they do, they have to speed up to e.g. 60 km/h to be of any practical value in city transportation. In doing so, they become quite lethal to everyone outside a car – pedestrians, cyclists and motorists – and very dangerous to everyone else, including the driver. This is worth stressing because it is not an obvious conclusion: if cars didn’t take up 20-40 square metres of space, traffic could flow more smoothly, lower maximum speeds could be used to achieve the same travel times and everyone’s safety would be dramatically improved. To illustrate with an idealized example, completely replacing the car fleet in a typical modern city with a pedal-assist bicycle fleet would cut maximum travel speed in half, reduce danger to all participants in traffic by a few orders of magnitude, maintain or reduce average door-to-door trip time, would not need a rigid, complicated legal framework and signalization infrastructure to do it and would make most parking lots obsolete. People would occasionally get wet, though. In 2005, 597 people died in Croatia (4.5 mil. inhabitants) in traffic accidents and about 200 became handicapped. How many would we consider acceptable? A 1000? 2000? 5000? The global traffic accident death toll is 1.2 million people, with 50 million injured. It sounds like quite a large number to shrug off as “that’s just how things are”.

So cars require a “lot” of space and this is generally understood, but the topic rarely gets discussed into any detail. What you find when you do look into it is that numerous sources quote numbers between 30% and 70% of urban surfaces dedicated to car traffic. A different way of looking at it is that a single bus on a highway replaces roughly 2 km worth of cars with 2 passengers each. If we didn’t waste all this space on cars, cities could be at least 20% smaller, land would be somewhat cheaper, outer neighbourhoods would be less far away from the centre, less land would be stripped of its natural biota and having to spend less time in traffic, people would be left with more free time to use as they desire. To add insult to injury, most cities were largely built without (too many) cars in mind and then retrofitted to poorly accommodate today’s traffic. Athens, Santiago de Chile, México City, Bogotá and many other multi-million inhabitant cities introduced a congestion management “even-odd” rule: half the cars can be used in the town centre on odd dates, and the other half on even dates. London, Stockholm and others introduced strict control and congestion charges on city centre entrances.

Car transportation requires immense up-front investments from both the community (roads, parking lots, a rather complex legal framework…) and drivers (it takes about 15 average Croatian salaries to buy an entry level car). As can be expected, the size of this investment makes car owners rather averse towards anything which would reduce the return on investment or make the investment less appealing – people want to enjoy their cars once they obtain them and don’t want to hear much talk of “a better way”, whatever it may be.

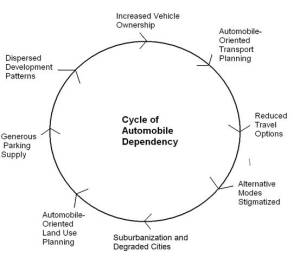

To drive the final nail in the coffin, all societies strive for progress, including an increase in purchasing power. As purchasing power increases, so does the number of cars per capita (historically). Consequentially, the problem can only get worse: more people will want to buy more cars, not less. Either cities will have to be designed and built completely around cars or a different mode of transportation will have to replace them. Car owners represent about 13% of the world population, but they use more than half of produced fuel. What happens if another 10-15% of the population decide they also have a right to a car, or two, or three? It appears we are about to find out. China plans to create 2 cities with a million people each each year for the next 20 years. Purchasing power is growing there and in India as well. The success of cars is, in fact, also their doom: the more there are in any given city, the closer the system comes to collapse due to reduced mobility and space availability.

With regard to pollution, a small car produces 130 kg of CO2 during a 1000 km drive. An average person uses 0.5 kg of oxygen per day and since oxygen makes 72% of the mass of a CO2 molecule, the car spends about the same amount of air as an average person breathing for 6 months. The transportation status quo is wholesale trade of oxygen for CO2, CO, NO2 and the rest of the chemical mix, just to get from point A to point B. It is very easy to forget or ignore that the atmosphere we enjoy was created over millions and billions of years and that – on a geological scale – we have only just arrived and spoiled it for the rest of the live world in a matter of two centuries of extreme industrialization. It is easy to forget because, well, “where would we get to worrying about such grand things we can’t influence anyway?” “What kind of difference can it possibly make if I drive or do not drive a car?”

Cars easily use 8 litres of petrol per 100 km when used in a city. A litre contains about 10 kWh of chemical energy, meaning cars spend roughly 80 kWh to travel 100 km. A cyclist travelling 30 km/h typically uses around 1 kWh per 100 km, although it can be much less with specialized bicycles. This means that a car uses about 80 times as much energy as a bicycle, in the typical scenario when it is used to transport a single driver within a city. Oh, and in an urban environment, the speed is quite comparable: sometimes the car is faster, but as often as not, a bicycle can beat it to the destination. A full electric train uses 1.5 kWh per 100 km and taking everything into account, it should probably be the transportation system of choice for medium length trips. Trains can travel faster than small aircraft without having to spend energy to keep their entire weight up in the air.

Speaking of alternatives, there is a bit of a chicken and egg problem to resolve. The current alternatives are not very appealing so there is a strong incentive to go with what we are taught is the default option – another car. Bicycle lanes don’t exist or don’t make any sense, there are no bicycle parking spaces, all the car traffic makes it dangerous and public transportation has its own drawbacks. However, it is car traffic that gets between 2 000 and 4 000 Euros per year per driver of investment, far more than all other forms of ground traffic – combined. Imagine if you will, what public transportation might look like with a 3 000 Euro yearly subscription fee (currently about 300 Euro/year). For a city like Zagreb (800 000 inhabitants, 500 000 cars), this would mean that public transportation services would have at their disposal no less than 1.5 billion Euros to organize transportation for its citizens. It is a bit difficult to imagine what might be done with that kind of money because (among other reasons) nothing at near that scale has ever been tried.

About a quarter of the total energy a citizen of Great Britain spends is spent on cars and similar numbers hold true for the rest of the western world. This is what should motivate people to reduce and stop driving cars: giving up cars immediately reduces personal energy footprint by no less than a quarter! Drop air travel as well and it is down to 50% or less of today’s average consumption: food for thought…

I have already mentioned the amount of space wasted on cars, but there are other efficiency concerns to add. The average car spends about 95% of its lifetime parked in front of a building. 80% of cars in traffic have a single passenger on board. Lugging a tonne of metal and plastic just to get around town is a ridiculous use of resources to accomplish this specific goal. Producing such a big and complicated machine requires a lot of technology, time and resources, all with a sizeable environmental toll. Any energy loss gets multiplied by a factor of 15 or more because that is how much heavier a car is compared to its passenger. In summary, on the rare occasions when the vehicle is not parked in front of a building, it has a useful load factor of less than 10% and requires several times its size of space on the road to drive relatively safely. Under which circumstances can that be called acceptable efficiency?

Oil, the source of the car’s pervasiveness, is a rich soup of carbon-based compounds used in almost everything we see and use around us: paraffin, artificial fertilizers, all types of plastics, endless industrial chemicals, asphalt, pesticides, tires, medicine etc. Burning a lot of it on the road is a certain way to make these goods costly or hard to produce. However, while we could survive without asphalt, the same cannot be said about food. In 1940, it took one calorie of fossil fuel energy to produce 2.4 calories of energy in the form of food. 1974 was a turning point: that year, the ratio was 1 calorie of fossil fuel energy for 1 calorie of food. Today, huge amounts of energy and artificial fertilizers are used to work the land, irrigate and package food, transport it over thousands of kilometres to its target markets, refrigerate it etc. All this contributes to a ratio of 10 calories of fossil fuels for every calorie we get from the food itself. In terms of energy, we are eating oil and as it seems, there is not much of it left. As we hail the birth of the 7 billionth person alive today, we are looking in the face of a large scale humanitarian disaster in the decades to follow and the last thing we should be doing is burning up a key food production resource to get to the theatre on a Saturday night.

It may be worth spending a few words to explain some of the reasons why we seem to ignore global problems such as cars so well. The place to start from is our biological heritage. Man can comprehend time and space in a very specific and limited manner. Man evolved as a mammal, travelling up to tens of kilometres per day, living tens of years. Because of this, man is fundamentally poorly capable of comprehending concepts like “a million years”, “10 000 km” etc. Science provides a vocabulary and logic to work with such concepts, but basically, we really have no conception of what a century is, let alone a millennium or a longer time span. We are good at noticing and reacting to short-lived processes: leaves shimmering in the wind, an animal moving, a rock falling – all of these are processes where it was important for us to be able to notice and react quickly to to be able to survive. This is an important consideration because people do not consider a change taking a 100 years quick, but compared to e.g. millions of years necessary to form an atmosphere like the one we enjoy or to form the flora and the fauna as it existed up to a few hundred years ago, it is just a metaphorical blink of an eye. Looking at it from this perspective, modern civilization changed the face of the planet in an instant.

“The face of the planet” – that is the other dimension with which people have trouble with. The only way we can think of the whole world is on a very abstract level. It is very difficult to get a feel for what “trillions of cubic meters of oil or oxygen” represent: the scale of these things is too far from anything we evolved to cope with well. These matters of scale make it very difficult to be very worried by daily changes we make in the world we live in. It is difficult to get a feel for what it means to burn 1500 billion litres of oil over the course of 2 centuries, topped off with coal and natural gas use. It is difficult to conceive the amount of CO2, sulphur and other compounds released as a side effect of this process. Importantly, it is difficult to come to terms with the fact that there are now so many of us on the planet that every trend of global proportions – especially one as important as transportation – has to be carefully scrutinized with regard to environmental impact and sustainability in general.

There are psychological consequences of a car-oriented culture, as well. One of them is an undeniable, obvious rise of stress people feel when close to intense traffic. The stress, I will venture a guess, comes partly from the extreme amounts of noise car traffic generates. Imagine starting a car engine in your living room and pushing the accelerator pedal: it would overwhelm all other sound in the room. Actual traffic noise is produced by possibly tens or hundreds of nearby cars and effectively doesn’t stop. A high noise level invariantly increases stress which when present daily, can cause significant health problems.

However, noise-caused tension is not the most important psychological problem related to cars. Road rage is a phenomenon which hardly exists outside of motorized road transportation. It is my impression that road rage is caused by a few unfortunately well aligned factors. The first is that errors in traffic are extreme health hazards so the stakes are high. The second is that when someone makes a mistake, almost nothing can be done: you can’t help but get excited because of the prospect of harm and you can yell or explain to offenders how they should have behaved, but when there are countless other drivers out there, you can only expect to be put into harm’s way again and again. We are extremely poorly adapted to handle that kind of mindless repetition of serious errors. Thirdly, while fundamental driving skills are simple, everyday driving is a relatively complicated process with lots of small optimizations. One can always learn more and we tend to expect the same or better skills in most other drivers. We not only expect this, we require it and when it doesn’t happen, it annoys us. Contributing to the annoyance is the level of interdependence between car drivers: cars are large and poorly manoeuvrable vehicles so they are frequently blocked by other cars in parking lots, slowed down by traffic in front, pushed by traffic behind etc. Finally, a lot of people are in a hurry when driving, they are tense because of the prospect of arriving late and therefore have severely limited tolerance for other drivers’ clumsiness. Having said all of this, it is a bit surprising that road rage is not a more wide-spread phenomenon. I would love to read a proper psychological research paper investigating the above assumptions.

A world with much lighter, slower, agile vehicles (the obvious example being bicycles) would reduce or do away with most of the above causes of road rage: virtually no noise, no serious physical threats, reduced driver interdependence which reduces the importance of other people’s mistakes, better arrival predictability which reduces unplanned delays…lots of things one can only dream of living in an average city.

Finally, there is the very mundane and unjustly important consideration of money. Looking at car sales, as a rule, the key criteria people take into consideration are car features and price of purchase. However, a relatively standard car in Europe now costs around 15 000 EUR. Assuming 12 000 km per year and current oil prices (1.5 EUR/L), 7 L per km average efficiency, 1000 EUR per year for basic and additional insurance, 600 EUR per year for various repairs and replacements and a 15 year life, its lifetime TCO is…57 900 EUR. In other words, every 5 years car owners spend as much money on their cars as they did on buying the machine in the first place. And that is without interest when savings aren’t enough to buy the car, without medical or other expenses you get from possible injuries in accidents, without the cost of time to manage the car etc. The one thing car owners can’t afford to seriously think about is TCO and the fact that people ignore future pain much more easily than immediate pain makes a lot of room for serious consequences. If the advertisement said “35 000+ EUR (over 5 years)” instead of “On sale: 14 999.99 EUR” as it says now, what would car sales look like? What would it mean to you?

To return to the introduction, electric cars are not going to save anyone or anything. They (like any other type of car) cannot be produced in large enough quantities, they are extremely resource hungry in terms of production and use and they are still very dangerous. One to two thirds of our urban surfaces are dedicated to car traffic, our cities constantly crave for more space to push all the traffic through, but there is no end in sight to the total global number of cars. If today’s global car fleet was a fleet of electric cars, it is far from clear that we could produce enough energy to power them without fossil fuels for at least the next few decades. If fossil fuels are going to power them in any significant part, than any actual global benefit will have been evaded other than maybe making drivers feel a bit better about themselves.

What electric cars do is cloud the issue, and the issue is that cars no longer make any sense as a mass transportation solution (if they ever did). Autonomous vehicles would be a welcome improvement, but they will not resolve the rush hour problem. It is my opinion (and one shared with a growing global community) that lighter, smaller, slower vehicles are the future of personal transportation and that we should look to public transportation for everything else. One thing that can be said as certainly as anything can be said is that if we stick with cars (and planes) till the bitter end, not being able to get to the theatre on a Saturday night is going to be the least of our worries.

Jedna misao o “Cars? Really? You can’t be serious.”